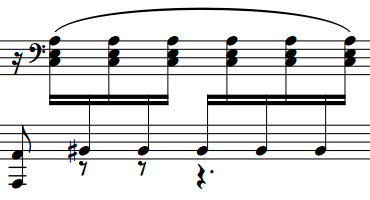

Beams are, simply put, compound flags: instead of drawing individual curly tails at the ends of the stems of successive notes, notes are joined by one or more thick lines. Engraving nerds only need apply.īeams first appeared in music notation around the turn of the eighteenth century, and trace their ancestry through the flags used to denote the rhythmic duration of shorter notes, and before that to the ligatures that denoted multiple notes to be sung to the same word or syllable, as shown in the now outmoded practice of beaming notes in vocal music according to the underlay of the words in preference to the rhythmic groupings of the meter. One of these latter areas is beaming specifically, the placement of beams relative to stave lines, and the amount of slant or slope that should be applied to beams given notes of different pitches, the amount of horizontal space occupied, and so on.Īdvance warning: this post goes into a lot of detail about subtle aspects of engraving practice concerning beam placement. This is a joke, of course, but perhaps only half of one: although there are certain aspects of how music notation should be presented that more or less everybody can agree on, there are many more that provoke lively debate. As a wise man once said, there are as many rules of music engraving as there are music engravers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)